Orthopaedic Surgeon

Shoulder Dislocation

What is injured when the shoulder dislocates?

The shoulder joint has the greatest range of motion of all the joints in the human body and therefore is at risk for dislocation. The humeral head is a ball which sits in a shallow, relatively small, cup shaped socket called the glenoid. The glenoid is made deeper by a rim of fibrocartilage called the glenoid labrum.

A loose capsule surrounds the bones of the joint and incorporates three main ligaments that help to hold the shoulder joint in place.

In addition to the capsule, there are four main muscles that span the shoulder joint. These muscles are called the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff muscles and tendons wrap around the humeral head to pull it more firmly into the glenoid fossa to improve the stability of the shoulder joint.

Instability occurs when the labrum is torn, the ligaments are torn or stretched, or when there are problems with the rotator cuff or the bones of the shoulder.

What happens when the shoulder dislocates?

Most commonly, the humeral head is forcefully levered out of the front (anterior) of the glenoid fossa and ends up forward and below the glenoid in the dislocated position. Shoulder dislocations occur most often when the arm is moved backward, pulling the humerus out of the glenoid socket.

Occasionally, The humeral head can be dislocated to the back (posterior) of the glenoid fossa. This can happen from a fall on an outstretched arm or from a direct blow to the front of the shoulder.

Sometimes, you can use your own muscles to “pull” the humeral head back into the socket. However, after the shoulder joint has been dislocated, the muscles of the shoulder will spasm or contract and not allow any movement of the dislocated humerus.

The dislocated humerus needs to be returned (relocated) to the glenoid fossa or socket as soon as safely possible. In most instances, you will need to be taken to an emergency department at a hospital. A physician will give medication to relax the shoulder muscles and then move the arm into a position to relocate the shoulder. A new series of xrays including a special xray known as an "axillary" view will be obtained to make sure the joint is reduced.

Treatment after dislocation consists of the use of a sling or shoulder immobilizer to rest the injured limb.

How is the shoulder joint “relocated”?

Right shoulder dislocated anteriorly. Image courtesy of Dr. Skelley.

Right shoulder after reduction. Image courtesy of Dr. Skelley.

Will my shoulder dislocate again?

Unfortunately, once you have dislocated your shoulder, the chances of it happening again are greater, especially if you are active in sports. Ligaments and tendons may stretch during a dislocation, making the shoulder unstable.

~ 90-95% Recurrence if less than 20 years of age (Rowe, McLaughlin, Hovelius, Arceiro)

~ 60-85% Recurrence if less than 30 years of age (Hovelius)

~ 95% if Bankart lesion present

Depends on age, athletic activity, fractures and bony lesions, underlying pathology

When is surgery necessary?

Surgery is indicated when the shoulder instability becomes a disability for the patient. The need for surgery depends upon the functional demands of the patient and the degree of instability present. Typically, surgery is not done unless a conservative program of exercise has failed. Patients who have repeated shoulder dislocations are the usual candidates for surgical repair.

What does the surgery involve?

Surgery attempts to restore an anatomical balance to the joint and address the problems that are causing the instability. The surgical repair tightens the stretched capsular ligaments and/or repairs the glenoid labrum which were torn at the time of the injury. In most situations, the surgery is performed using arthroscopic surgery techniques with small incisions around the shoulder.

A video demonstrating a labral repair surgery can be found here.

The goal of surgery is to restore stability while maintaining mobility and restoring pain-free functional use of the shoulder in daily activities as well as sports and recreational activities. Typical success rates for open surgery for shoulder instability vary from 90 to 95 %.

Bankart or Anterior-Inferior Labral Repair for Shoulder Instability

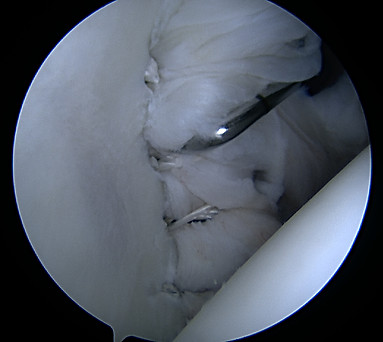

Viewing from the back of the shoulder to the front, the arm bone ball (humerus) is on the right and the cup of the shoulder blade (glenoid) is on the left. The probe is lifting up the torn labrum.

The two suture ends are retrieved through the same portal and pulled out of the way to allow for drilling.

A metal hook is passed through the labrum and a wire is passed through the hook to pass a suture around the laburm.

The anchor position is selected and the drill creates a tunnel for the anchor.

The anchor is placed holding the sutures in place and securing the labrum back in position to stabilize the arm bone in the cup.

The metal hooked prob pulls on the labrum (just like in the first image) and demonstrates that the tear is repaired and stable.

References

1. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):404-420. doi:10.1053/jars.2003.50128.

2. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part II: evaluation and treatment of SLAP lesions in throwers. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(5):531-539. doi:10.1053/jars.2003.50139.

3. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part III: The SICK scapula, scapular dyskinesis, the kinetic chain, and rehabilitation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(6):641-661.

4. Skelley, N.W., Smith M. Prevention of Labral Cuff Injuries in the Overhead Athlete. In John Kelly IV (Ed), Elite Techniques in Shoulder Arthroscopy. Springer. 2016. ISBN 3319251015.

5. Skelley NW, McCormick J, Smith MV. In-Game Management of Common Sports Related Joint Dislocations. Sports Health. 2014;6(3):246-255. doi:10.1177/1941738113499721.